Press

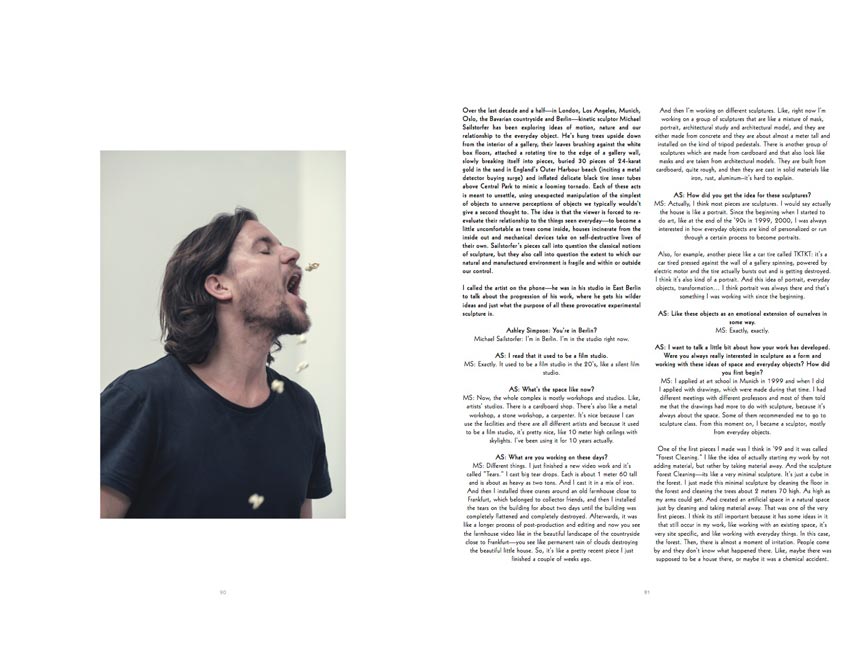

Ashley Simpson in conversation with Michael Sailstorfer

Interview for S Magazine, 2016

Over the last decade and a half—in London, Los Angeles, Munich, Oslo, the Bavarian countryside and Berlin—kinetic sculptor Michael Sailstorfer has been exploring ideas of motion, nature and our relationship to the everyday object. He’s hung trees upside down from the interior of a gallery, their leaves brushing against the white box floors, attached a rotating tire to the edge of a gallery wall, slowly breaking itself into pieces, buried 30 pieces of 24-karat gold in the sand in England’s Outer Harbour beach (inciting a metal detector buying surge) and inflated delicate black tire inner tubes above Central Park to mimic a looming tornado. Each of these acts is meant to unsettle, using unexpected manipulation of the simplest of objects to unnerve perceptions of objects we typically wouldn’t give a second thought to. The idea is that the viewer is forced to re- evaluate their relationship to the things seen everyday—to become a little uncomfortable as trees come inside, houses incinerate from the inside out and mechanical devices take on self-destructive lives of their own. Sailstorfer’s pieces call into question the classical notions of sculpture, but they also call into question the extent to which our natural and manufactured environment is fragile and within or outside our control.

I called the artist on the phone—he was in his studio in East Berlin to talk about the progression of his work, where he gets his wilder ideas and just what the purpose of all these provocative experimental sculpture is.

Ashley Simpson: You’re in Berlin?

Michael Sailstorfer: I’m in Berlin. I’m in the studio right now.

AS: I read that it used to be a film studio.

MS: Exactly. It used to be a film studio in the 20’s, like a silent film studio.

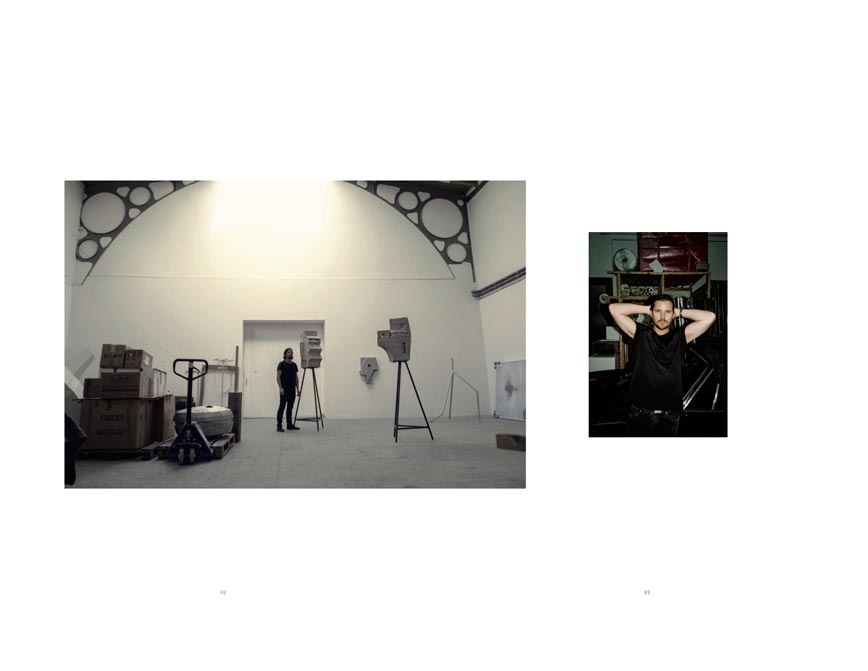

AS: What’s the space like now?

MS: Now, the whole complex is mostly workshops and studios. Like, artists’ studios. There is a cardboard shop. There’s also like a metal workshop, a stone workshop, a carpenter. It’s nice because I can use the facilities and there are all different artists and because it used to be a film studio, it’s pretty nice, like 10 meter high ceilings with skylights. I’ve been using it for 10 years actually.

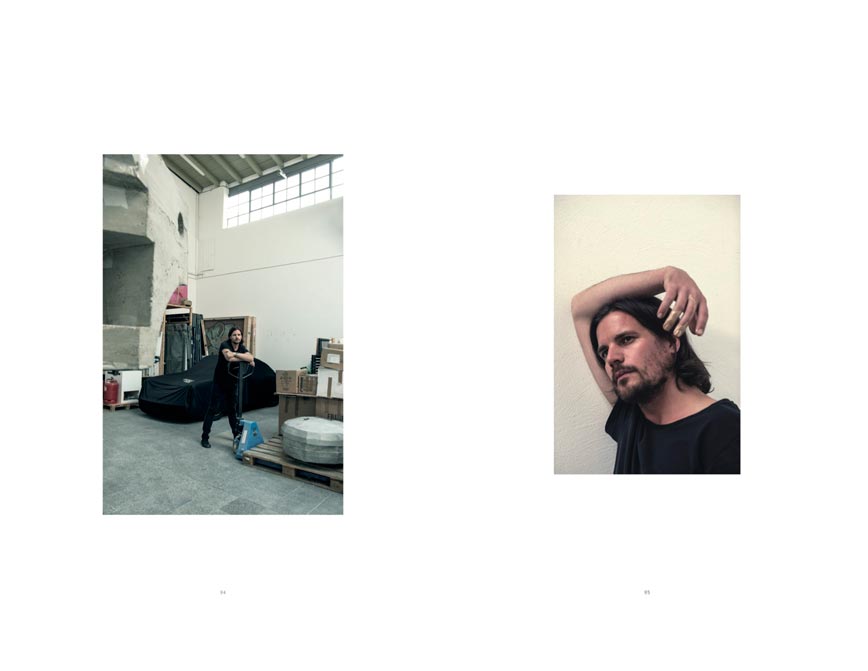

AS: What are you working on these days?

MS: Different things. I just finished a new video work and it’s called “Tears.” I cast big tear drops. Each is about 1 meter 60 tall and is about as heavy as two tons. And I cast it in a mix of iron. And then I installed three cranes around an old farmhouse close to Frankfurt, which belonged to collector friends, and then I installed the tears on the building for about two days until the building was completely flattened and completely destroyed. Afterwards, it was like a longer process of post-production and editing and now you see the farmhouse video like in the beautiful landscape of the countryside close to Frankfurt—you see like permanent rain of clouds destroying the beautiful little house. So, it’s like a pretty recent piece I just finished a couple of weeks ago.

And then I’m working on different sculptures. Like, right now I’m working on a group of sculptures that are like a mixture of mask, portrait, architectural study and architectural model, and they are either made from concrete and they are about almost a meter tall and installed on the kind of tripod pedestals. There is another group of sculptures which are made from cardboard and that also look like masks and are taken from architectural models. They are built from cardboard, quite rough, and then they are cast in solid materials like iron, rust, aluminum–it’s hard to explain.

AS: How did you get the idea for these sculptures?

MS: Actually, I think most pieces are sculptures. I would say actually the house is like a portrait. Since the beginning when I started to do art, like at the end of the ‘90s in 1999, 2000, I was always interested in how everyday objects are kind of personalized or run through a certain process to become portraits.

Also, for example, another piece like a car tire called TKTKT: it’s a

car tired pressed against the wall of a gallery spinning, powered by electric motor and the tire actually bursts out and is getting destroyed. I think it’s also kind of a portrait. And this idea of portrait, everyday objects, transformation... I think portrait was always there and that’s something I was working with since the beginning.

AS: Like these objects as an emotional extension of ourselves in some way.

MS: Exactly, exactly.

AS: I want to talk a little bit about how your work has developed. Were you always really interested in sculpture as a form and working with these ideas of space and everyday objects? How did you first begin?

MS: I applied at art school in Munich in 1999 and when I did

I applied with drawings, which were made during that time. I had different meetings with different professors and most of them told me that the drawings had more to do with sculpture, because it’s always about the space. Some of them recommended me to go to sculpture class. From this moment on, I became a sculptor, mostly from everyday objects.

One of the first pieces I made was I think in ’99 and it was called “Forest Cleaning.” I like the idea of actually starting my work by not adding material, but rather by taking material away. And the sculpture Forest Cleaning—its like a very minimal sculpture. It’s just a cube in the forest. I just made this minimal sculpture by cleaning the floor in the forest and cleaning the trees about 2 meters 70 high. As high as my arms could get. And created an artificial space in a natural space just by cleaning and taking material away. That was one of the very first pieces. I think its still important because it has some ideas in it that still occur in my work, like working with an existing space, it’s very site specific, and like working with everyday things. In this case, the forest. Then, there is almost a moment of irritation. People come by and they don’t know what happened there. Like, maybe there was supposed to be a house there, or maybe it was a chemical accident.

AS: What artists are you interested in within the context of your work, and also more generally?

MS: I think of course it’s visual artists. But also, music was also always a big inspiration. I like going to concerts and I like to see music. I think sometimes a concert stage might be the best sculpture anyway, because it has a huge presence in the space and I think it spreads out in the space and there’s also like this immediate interaction with the audience and the feedback. I think if I could make a sculpture that does something similar, that might be pretty good...

There are also visual artists which area always a big reference, starting from Marcel Duchamp, like how he used everyday objects and provocated since the beginning of the last century. Then, there’s Bruce Nauman of course, Gordon Matta Clark... [He has] one piece that is like a milestone. It’s called “Splitting.” He just took a regular house, like a one family house in the suburbs of New York, and cut the whole house in half. I’m really interested in how by doing this—cutting through the house—you’re actually hurting the house, or how it’s personalized or becoming like a mirror of yourself somehow.

Also, like Isa Genzken. I always liked her work—she always created a new language and reinvented a new practice. I think that’s always the most interesting part, always trying to do something new and interesting, challenging yourself, and not repeating yourself. I think that’s why she was always a big idol, as well.

AS: For your own work, how do you see the viewer or the audience interacting? What do you observe but also what do you hope for?

MS: I think art is always for an audience, and as I said before, I’m always interested in this interaction between audience and piece and also how a piece reacts to a space. For example, one piece is called “Reactor.” It’s just a block, a cube of concrete, not necessarily

big, and then there is one microphone imbedded in the concrete. I

cast this in the concrete. The microphone is connected to an active speaker next to the block of concrete and the block of concrete works like a pick-up, like an electric guitar. You set it on the floor and it picks up the vibration on the floor, the ambient of the space, and the more people who walk through the space, the louder the work gets. When the space is empty, then the piece is quiet again. And of course, it creates a certain aggression also. I’m interested in this presence of the piece in the exhibition space, and it’s not necessarily polite to the viewer. There is also a kind of confrontation.

AS: And do you have forms or ideas of either everyday objects or concepts related to that that you really want to explore in the future?

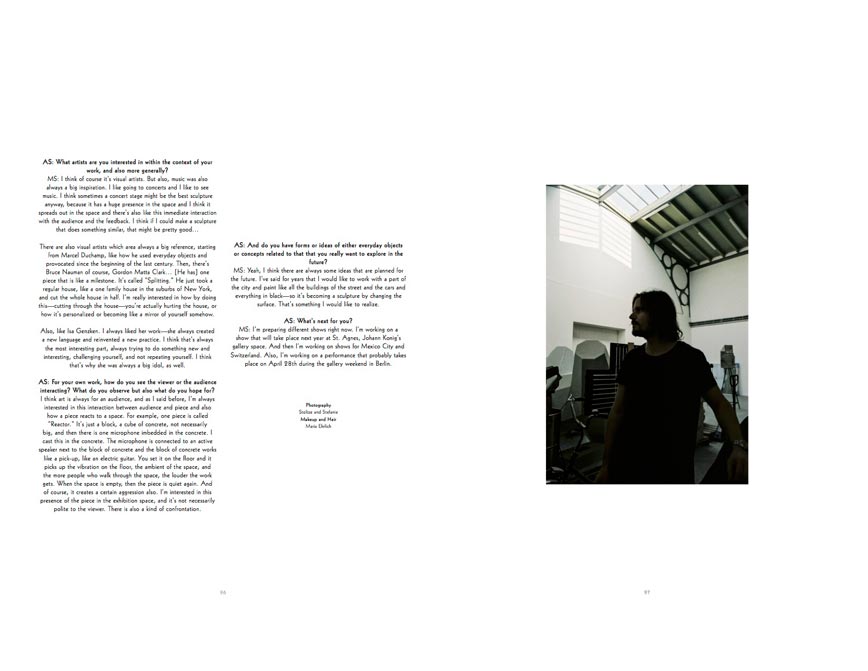

MS: Yeah, I think there are always some ideas that are planned for the future. I’ve said for years that I would like to work with a part of the city and paint like all the buildings of the street and the cars and everything in black—so it’s becoming a sculpture by changing the surface. That’s something I would like to realize.

AS: What’s next for you?

MS: I’m preparing different shows right now. I’m working on a show that will take place next year at St. Agnes, Johann Konig’s gallery space. And then I’m working on shows for Mexico City and Switzerland. Also, I’m working on a performance that probably takes place on April 28th during the gallery weekend in Berlin.